Scholar Explores Ascriptions to Shia Imams as a Source of Religious Authority

In her chapter titled “Rulers as Authors: ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and the Other Twelver Imams,” included in the volume Rulers as Authors in the Islamic World, historian Teresa Bernheimer explores how the attribution of literary works to the Twelver Shia Imams has functioned as a source of religious authority.

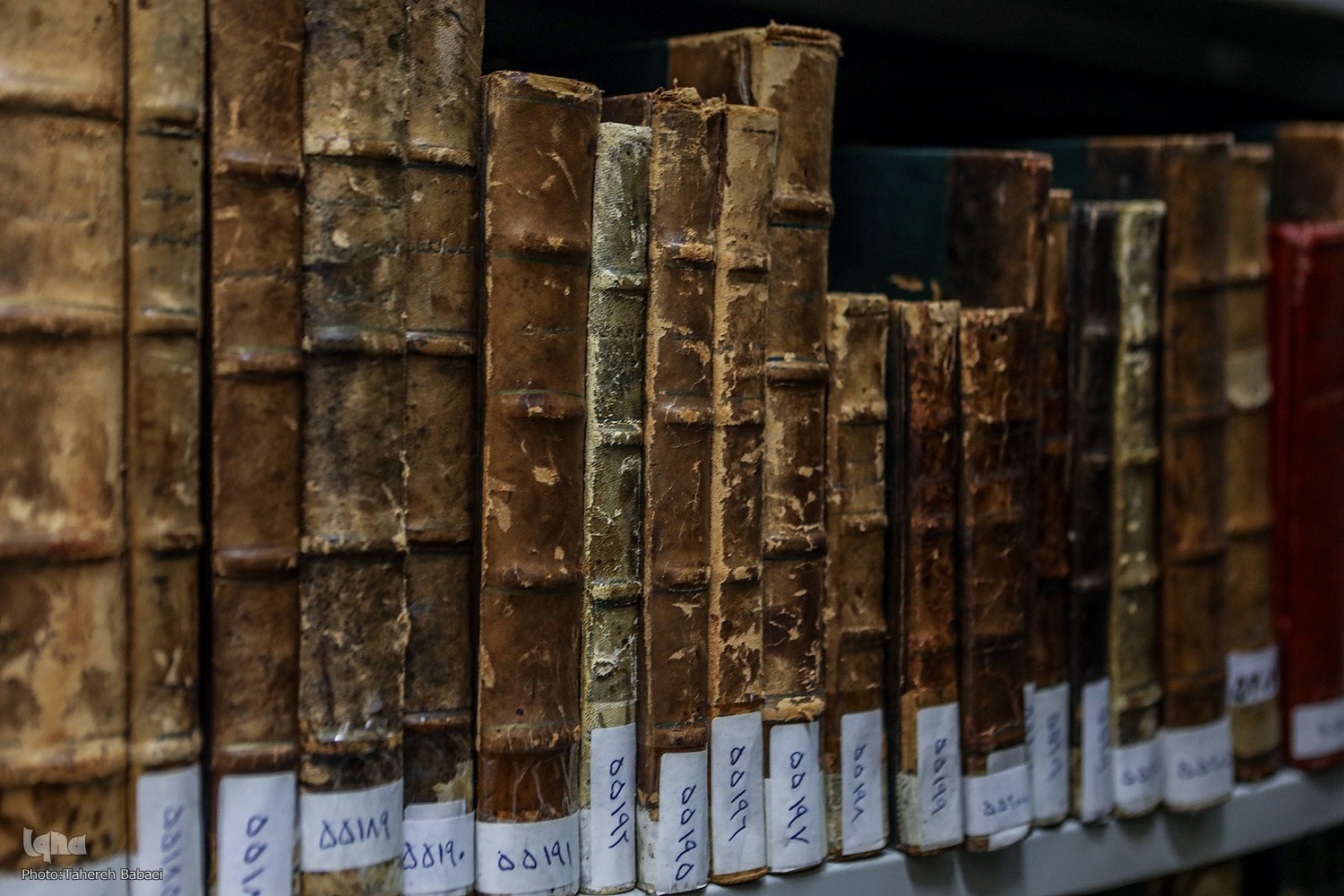

Through textual analysis and manuscript evidence, she offers an overview of the genres and themes associated with these attributions, while probing what it means to describe the Imams as “authors” within the Shia intellectual tradition.

In an exclusive statement to IQNA, Bernheimer explained the broader aims of her work:

“In the article 'Rulers as Authors: ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and the Other Twelver Imams', I sought to contribute to discussions about religious authority, authorship, and canon formation in Islamic intellectual history. My aim was to examine how the many ascriptions of texts to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and the other Imams of the Twelver Shia tradition functions as a means of textual authority and religious legitimacy, reflecting the Imams' role not only as a recipient of divine or esoteric knowledge, but as an authorial presence within the Shia tradition. I tried to give an overview of the astonishing variety of topics and genres ascribed to the Imams, and explore the purpose and context of these ascriptions.

Some of the works ascribed to the Imams are known only by title, some can be gleaned from citations in later works, and some are extant in manuscript copies: An exciting avenue for further study is the manuscript evidence: When do we first find certain attributions in physical form, how widely were they copied? A detailed examination of the surviving manuscript evidence would add a valuable dimension to the argument, helping us to chart the afterlife of these texts and to see more clearly the mechanisms through which authorial authority was consolidated.”

Read More:

Bernheimer opens the chapter by referencing Ibn al-Nadīm’s Fihrist, a 10th-century Arabic catalogue of books. While it lists Imam Ali (AS) and Imam Baqir (AS) among early Islamic figures associated with intellectual output, it notably excludes most other Twelver Imams as authors—a fact that she identifies as surprising given the large number of works later attributed to them.

“This absence is indeed surprising,” she writes, “later Islamic tradition, both Sunni and Shia, record a great number of works ascribed to the Twelver Imams.”

Her chapter does not attempt a comprehensive cataloging but instead provides a typology of these works, divided into thematic categories. These include Quranic exegesis, hadith collections, legal treatises, supplications, sermons, theological texts, medical manuals, poetry, and even writings on alchemy.

The chapter examines the different genres in which Imams are presented as authors. One category is exegetical works, where figures like Imam Baqir (AS) and Imam Sadiq (AS) are credited with interpretations of the Quran. Bernheimer notes that “exegetical knowledge of the Quran is among the central faculties attributed to the Shia Imams,” but highlights that surprisingly few complete commentaries are ascribed to them in full manuscript form.

In terms of legal texts, she discusses works such as Risālat al-Ḥuqūq (Treatise on Rights), attributed to Imam Sajjad (AS). She writes that it is “a short summary of the rights of God upon man,” and it is preserved in works from the 10th century.

Read More:

Another significant area is devotional literature, including the widely known al-Ṣaḥīfa al-sajjādiyya, a collection of supplications attributed to the fourth Imam. These works have been preserved in numerous manuscripts and translated widely.

Bernheimer also draws attention to sermons and sayings, most notably the Nahj al-Balāgha, a renowned collection of sermons attributed to Imam Ali (AS) and compiled in the 10th century by al-Sharīf al-Raḍī.

In her conclusion, Bernheimer points out that the Buyid and Safavid eras appear as crucial moments when Shia texts and their associations were consolidated and circulated more broadly.

The inclusion of works in non-Shia libraries, such as the Ashrafiyya in Damascus, reflects what she describes as “confessional ambiguity”—a veneration of the Imams that transcended sectarian boundaries.

The chapter ends with a reflection on the continuing relevance of this research, especially in light of digital tools that can facilitate manuscript analysis. Bernheimer writes, “The new possibilities of research supported by the digital humanities in our field make this an excellent topic to gain a fuller understanding not only of the formation of Shia scholarship, but of the historical development of Islamic learning more generally.”

Please note that the content reflects the views of the scholar and does not represent the views of the International Quran News Agency.