Int’l Law Not Strong Enough to Stop Affronts to Holy Sanctities: Ex-UN Rapporteur

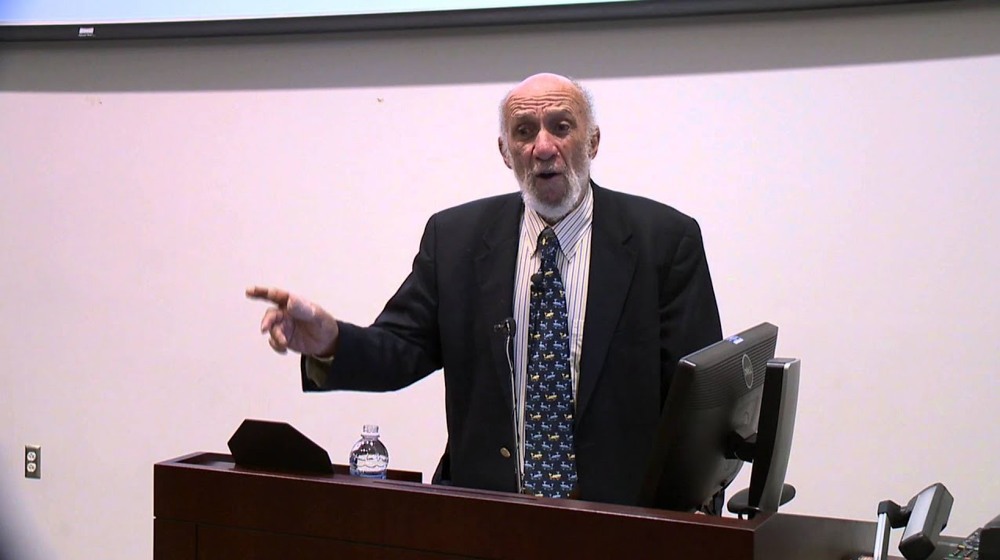

“In any meaningful sense, I do not think international law is strong enough in relation to these issues at the interface of human rights and the sanctity of religious values and practice to impact behavior at the level of sovereign states,” Richard Anderson Falk, a professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, told IQNA commenting on the ongoing acts of Quran desecration in Sweden and Denmark.

The following is the full text of the Interview:

IQNA: Over the past month, the Holy Quran has been subject to acts of desecration multiple times in Sweden and Denmark. What is your take on these acts?

Falk: As a first line of response, I would interpret these acts of desecration as an aspect of the assault by right-wing extremists on secular democracy in Europe. The fact that Sweden was the principal site of these incidents involving the Quran is significant as Sweden was previously viewed as the most progressive social democracy in Europe with a generally permissive atmosphere, but not a breeding ground of extremist political movements, although quite conformist in its skepticism about religion. The anti-migrant right (but not the desecrating extremists) has won the most recent national elections and currently governs the country.

A more proximate cause may be connected with a far-right reaction of anger and fear to the leverage displayed by the Muslim-majority state of Turkey in relation to Sweden’s official effort to join NATO almost 75 years after the alliance was formed, an undertaking itself indicative of this Swedish swing to the right. The desecration incidents from this perspective should be viewed as directed both at the Swedish Government for its apparent willingness to bargain with Turkey on the issue, tarnishing its right-wing credentials by doing so and at Islamist Turkey encroaching on European cultural space.

Of course, these explanatory remarks are highly conjectural on my part, but they do seem consistent with the behavioral patterns of these extremist fragments (the leader of these events was a Danish-Swedish lawyer and political extremist, Rasmus Paludan, head of the Strum Kurs (hardline) political party that operates in both countries and managed to win only 1.8% of the vote in the 2019 Swedish election, which was not enough to qualify for the Parliament). It is relevant to note that Turkey has issued an arrest warrant charging Paludan with responsibility for a desecration incident posing security threats to the Turkish Embassy in Stockholm earlier this year.

In general, anti-Islamic extremism is both an internal and international challenge to the European Union, which wants peace and stability within Europe without giving rise to blowback effects in Muslim-majority countries that take offense. For instance, Qatar, although not targeted in Sweden, removed all Swedish products from its largest market, Souq Al Baladi, and a number of other states have withdrawn their ambassadors from Sweden as expressions of Islamic solidarity. The EU remains reluctant to challenge by recourse to law freedom of expression standards that prevail in several of its leading member states. I think Josep Borrell, the EU minister for foreign policy, summed up the official response accurately, although elliptically, by saying on the subject of Quran desecration, ‘Not everything that is legal is ethical.’

A similar approach was evident in the July vote at the UN Human Rights Council of a resolution condemning the desecration of the Quran by the negative votes of the leading European states (UK, Germany, France, joined by the USA). Although these governments deplored the Quran desecration, they refused to support the HRC resolution, which they claimed was an unbalanced text, endangering freedom of expression, and unacceptably close to prohibiting all forms of blasphemy. The overall vote on the resolution of the 47 HRC members was 28-12 (with 7 abstentions). Most HRC members from Africa, as well as China, supported the resolution. The HRC’s official release described the resolution this way: “The Human Rights Council July 12th adopted a resolution in which it condemned and strongly rejected any advocacy and manifestation of religious hatred, including the recent public and premeditated acts of desecration of the Holy Quran.” The body of the resolution called upon states to enact national laws of similar intent, but seems unlikely to have the slightest effect on the 12 states voting against the resolution.

'Extremist seek media attention'

IQNA: How can we stop such acts and help promote interfaith respect and peaceful coexistence among followers of various faiths?

Falk: There is a paradox present: The harder efforts are made to stop such horrible behavior by Islamophobic and right-wing extremist groups the greater is their temptation to persist in such action. In the short term what these groups seek is public recognition and media attention, not power. These are displays of symbolic politics at its worst as it champions ethnoreligious supremacy as the alternative to coexistence with dark and evil forces. Quran desecration also serves as a recruiting strategy that attracts those deeply dissatisfied with their lives and receptive to blaming the Islamic other.

And then there are counter-pressures from dogmatic secularists not to alter behavior in response to outcries from foreign religious sources. Such secularists, whether openly or not, seek to insulate from governmental interference anti-religious speech and symbolic acts, however hurtful, and even when they come from extremist sources. In the current historical setting of Europe, desecration acts especially those directed at theocratically governed states such as Turkey, enjoy a high level of silent approval from a hostile populace. What is often criminalized and harshly punished as blasphemy in some Muslim-majority states, for instance, Pakistan, is celebrated as protected speech in the secular West.

Inter-faith dialogue if conducted at high enough levels at least promotes a better understanding of cultural and religious differences among countries and civilizations, but the root cause is ethnically and religiously driven extremism, which at its worst sets the stage for fascist styles of governance, which happened in post-World War I Europe. A further step in moderating such tensions is to mount a major international effort to improve the material conditions in the least-developed countries that would have an almost automatic effect of discouraging massive migratory flows now arising from impoverished societies, conflict zones, and climate disaster. The political resonance of Quran burning is emotionally linked to the backlash against these patterns of migrating peoples fleeing from alien cultural traditions for economic, political, and ecological reasons. We all need to remember that most people do not leave their homelands unless national living conditions become intolerable.

With the planet challenged currently by ecological and geopolitical threats to species survival, only ways of acting on a global scale to improve procedures of conflict resolution and inter-governmental cooperation can have any chance of weakening incentives of extremists and those most acutely alienated to carry out attacks against scapegoated religious minorities.

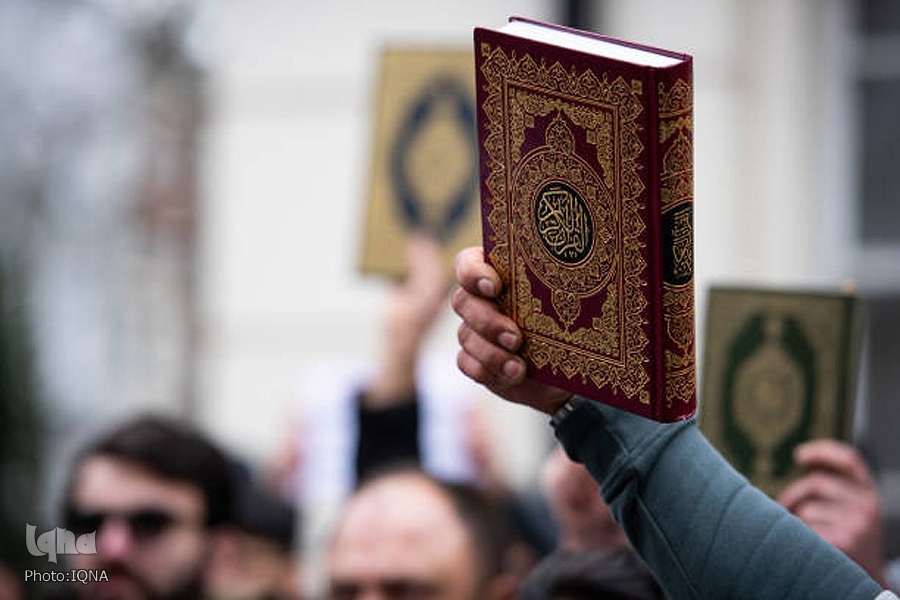

Acts of Quran desecration in Sweden and Denmark has prompted strong protests in the Muslim world.

IQNA: Who or what group do you think is behind the affronts? Or who or what group benefits from them?

Falk: As suggested throughout, those affronts to Islam emanate from the extreme right that are drawn to fascist beliefs and practices as historically contextualized in relation to time and place. For Hitler and Naziism it was Jews as a people, in the United States those seeking to restore white supremacy it is African Americans, and after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, it was Islam while for Donald Trump it has become migrants, especially those entering the country unlawfully.

Affronts to Islam emanate from the extreme right that are drawn to fascist beliefs and practices

Extremists tend to flourish in national settings where their acts, while superficially condemned, are congruent with the beliefs and biases of large parts of the population. I feel the danger in Europe arises from the extreme right gaining further political strength through such acts of demonization. The rise of secular populism and its autocratic leaders around the world has produced suppression of religious freedoms of Muslims even in many countries within the Arab world, and more pronouncedly in Modi’s India with its drive to achieve Hindu supremacy and even Myanmar where the military leadership in alliance with the Buddhist majority has ruthlessly suppressed Muslims in the federal state of Rakhine where the Muslim minority, the Rohingya people predominated.

IQNA: Swedish and Danish officials have deplored the desecration of the Quran, saying, however, that they cannot prevent it under constitutional laws protecting freedom of speech. What are your thoughts on this as an international lawyer?

Falk: Although there is some support for the view that desecration of the Quran and other holy books violate international law, and a July 25 UN General Assembly Resolution drafted by Morocco and adopted by consensus so declares, it is not regarded by most governments in the West as obligatory and would encounter strong resistance if implemented in national criminal codes and operational practices. The emphasis of the resolution is suggested by these words, deploring ''all acts of violence against persons on the basis of their religion or belief, as well as any such acts directed against their religious symbols, holy books, homes, businesses, properties, schools, cultural centers or places of worship, as well as all attacks on and in religious places, sites and shrines in violation of international law.''

There is an underlying jurisprudential problem that is rarely discussed. In the West, meaning in Western Europe and North America, the separation of church and state followed upon decades of religious warfare within Christianity. From the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 onwards until the present the dominant political tradition in various formats has embraced the separation of church and state, including seeking to make the legal order autonomous, that is, resistant to overt religious oversight and direct interference. To be sure, there have been inconsistencies on the level of practice, especially on such symbolic issues as the reproductive rights of women and the character of conscientious objection to obligatory service. In contrast, it is my understanding that Islamic values decry such a separation, and believe strongly that the law should follow the precepts of religious guidance or oversight.

We must be careful not to fuel such extremists' passions and dark ambitions by giving them the media attention they so desperately crave

In any meaningful sense, I do not think international law is strong enough concerning these issues at the interface of human rights and the sanctity of religious values and practice to impact behavior at the level of sovereign states. Perhaps, the struggles for species survival will build enough support for trans-civilizational unity on behalf of the global public good, which has been put forward by some, including me, as a unique instance of a ‘necessary utopia.’ In the interim, there will be clashes of the sort embedded in diverse ways of handling the desecration of the Quran, the scriptures of other faiths, and holy sites and objects generally. In fashioning responses, we must be careful not to fuel such extremists' passions and dark ambitions by giving them the media attention they so desperately crave.

Professor Richard Anderson Falk is the author or co-author of 20 books and the editor or co-editor of another 20 volumes. In 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) appointed him to a six-year term as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on "the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967”.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview are solely those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the view of International Quran News Agency.