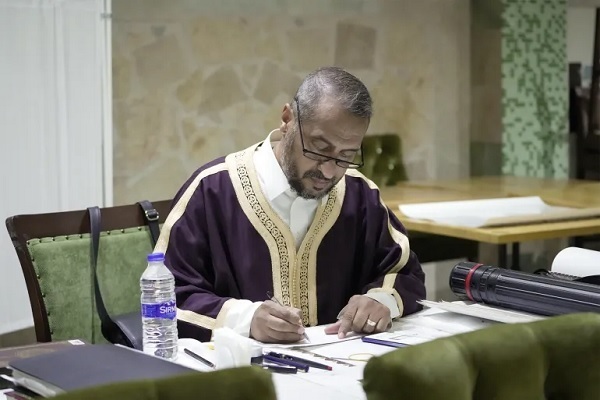

Libyan Calligrapher Overcomes Hardships to Transcribe Quran

Al-Zanati’s journey in calligraphy began in childhood, when his schoolteacher—also a relative—noticed his handwriting and made a pivotal remark.

“My teacher Ali bin Ali, who was my father’s cousin, told me, ‘You are a calligrapher. Your handwriting is beautiful,’” Al-Zanati told Al Jazeera Arabic. “That was the first time I heard the word ‘calligrapher.’ It changed everything for me.”

Born into a family where art held cultural significance, Al-Zanati was mentored by a series of Arabic calligraphers, including Ibrahim Al-Zanati and later, Mahfouz Al-Buaishi, who he credits with shaping his artistic path.

Read More:

Another turning point came through a connection with Abu Bakr Sassi, the calligrapher of Libya’s Mushaf al-Jamahiriya, a version of the Quran published in 1982 based on the Qalun narration. “He told me, ‘One day, God willing, you will become a Quran calligrapher.’ His words stayed with me,” Al-Zanati recalled.

Through his journey, Al-Zanati also worked with Sadiq Al-Zaghadani, another calligrapher, accompanying him on trips to Mali and Uganda to teach Arabic calligraphy. These experiences, he said, were critical in developing his artistic and professional identity.

Realizing the Dream

“The words of Sheikh Abu Bakr Sassi never left me,” Al-Zanati said. “When the time was right, by God’s grace, I began working to bring this dream to life.”

At the time, Libya was grappling with political instability, and funding such a project was a significant challenge. “I searched for years for someone to invest in the idea,” he said. Eventually, he approached Libya’s General Authority for Religious Endowments (Awqaf), the governmental body overseeing religious affairs.

Al-Zanati submitted a formal request in March 2017. “I explained the need to fill a gap in Quranic calligraphy in the Qalun narration,” he said. The project was approved, a supervisory committee was established, and the necessary licenses for printing and distribution were secured.

Tools, Techniques, and Family Support

Calligraphy, particularly of the Quran, requires meticulous planning and execution. Al-Zanati opted to use a fountain pen after consulting with other artists. “The pen must match the line length and level of precision. The type of desk, the weight of the paper—whether for printing or handwriting—all mattered,” he explained.

His son, Mohammed, played a crucial role. “He managed the technical aspects of the project. His support saved me time and effort, especially when the project moved into the digital phase,” Al-Zanati said, adding that technology played a key role in facilitating the production.

Enduring Personal Struggles

The transcription was Al-Zanati’s first experience writing the Quran in its entirety—a process requiring exceptional accuracy. “There was no room for error,” he said. “I had to be mentally focused and technically prepared.”

The journey was also marked by significant personal hardship. “My father was battling cancer, and we spent three years in Turkish hospitals,” Al-Zanati said. “At the same time, I was working on the Quran. Despite the emotional strain, I fulfilled both duties.”

Read More:

His family faced additional trials during the COVID-19 pandemic. “My wife became ill, and I had to juggle caring for her and our children while continuing the project,” he said.

The most painful blow came from his workplace. Al-Zanati had been working in Libya’s customs department. Despite what he described as a prior agreement to dedicate himself to the Qur’an project, he was dismissed due to extended absence.

“I was shocked,” he said. “The world was shut down because of COVID. Even schools and most government offices were closed. Tripoli was going through conflict. I expected support, not punishment.”

Read More:

Al-Zanati said he never sought personal recognition but was driven by a larger purpose. “Everyone has a role to play in life. Mine was to enhance Quranic calligraphy,” he said.

In Libya, Quranic schools and memorization centers (known as Dar al-Tahfiz) are central to children’s religious education, especially during holidays. “There was an increasing need for a locally produced Mushaf. I believe this work met that need and had a real social impact.”

4272584