From Patience to Moral Courage: American Scholar on What Lady Fatima Teaches Today

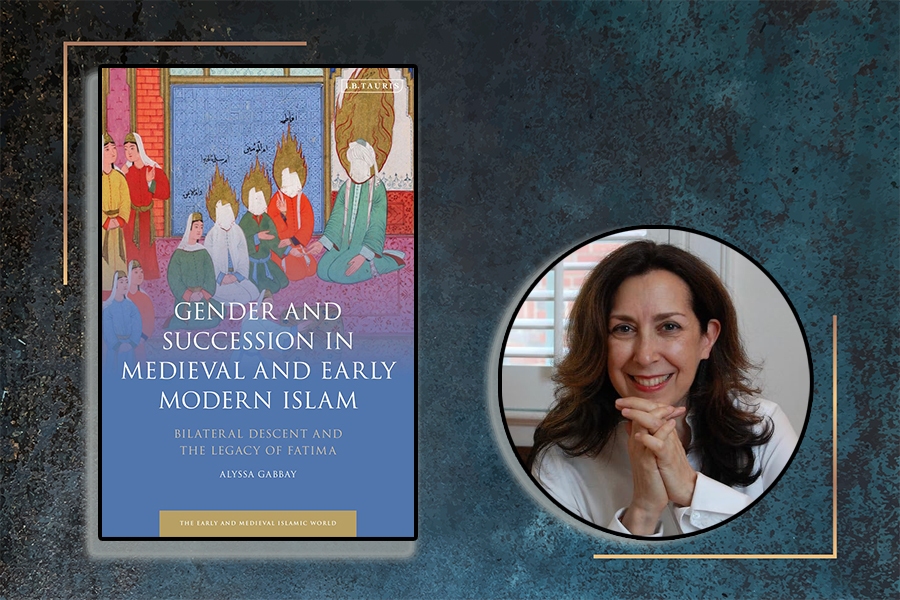

Alyssa Gabbay is an assistant professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, specializing in early Islamic history.

Her book, Gender and Succession in Medieval and Early Modern Islam: Bilateral Descent and the Legacy of Fatima, examines Lady Fatima’s pivotal place in Islamic thought.

Speaking to IQNA, Gabby named “patience under suffering” and “speaking out against injustice when it is necessary” as two of the lessons that women can draw from the life of Lady Fatima.

What follows is the full text of the conversation:

IQNA: Muslims across sects revere Lady Fatima as the Prophet’s beloved daughter and a paragon of faith, modesty, and strength. From your study of early Islamic sources, what aspects of her life or personality stand out most vividly to you?

Gabby: There are so many aspects of Hazrat Fatima’s life and personality that stand out to me that it is quite difficult to pick out just a few. Her dedication and devotedness to the Prophet is definitely an important one – she seems to have been a steadfast support for him at times when he greatly needed it.

I am also struck by the Muhammadan light that is supposed to have radiated from her, and is depicted as emanating from her in many images – a sign that she, too, receives the primordial light that is associated with God, and in many cases represents ‘ilm, or knowledge.

Read More:

The sermon that she delivered before the Muslim community, in which she sharply criticizes the direction the Umma is taking, and lays claim to the property of Fadak, is also a very striking demonstration of her spiritual authority, even though it is a more divisive issue for Muslims.

Finally, the fact that, via the angel Gabriel, Fatima is supposed to have been the recipient of a mushaf – a miraculous, divinely inspired text that is associated with considerable authority and power – solidifies her stature as one who, if not an imam or a prophet, bears close similarities to them.

IQNA: In your research, did you find evidence that Lady Fatima’s example impacted how later Muslim societies viewed women’s religious or moral authority?

Gabby: Absolutely. Just to give one example, Shi’i scholars such as Ibn Babawayh (al-Shaykh al-Saduq) and al-Majlisi both cite Fatima’s Sermon on Fadak in their collections of hadith, which indicates that they saw her as a model for behavior. She is seen as someone who can authoritatively explain the reasoning behind divine ordinances such as prayer and fasting.

IQNA: Some scholars argue that Lady Fatima embodies both maternal compassion and social activism. Do you think these dimensions of her character are sufficiently recognised in contemporary Islamic discourse?

Gabby: I think that her role as an activist and as a spiritual and temporal leader are being increasingly emphasized by contemporary scholars and that this is a good thing. It can easily coexist with her role as a compassionate mother; the two are not mutually exclusive.

IQNA: Some readers, especially among Shia audiences, might feel that the spiritual significance of Lady Fatima goes beyond social lineage. How do you respond to those who feel that purely historical analysis may overlook that sacred dimension?

Gabby: I wholeheartedly agree that the spiritual significance of Fatima goes far, far beyond that of social lineage. It was not my aim, in this book, to try to capture the entirety of that spiritual significance, but rather to highlight one element of it that may have been overlooked.

There are other excellent books that are more geared to capturing her spiritual significance in a general sense and I would highly recommend those to readers.

Read More:

As an academic scholar writing for an audience that is at least partly made up of secular people, I am always striving to maintain the proper balance between scholarly detachment and appreciation of the sacred. I can’t say that I always achieved this balance, but I did my best!

IQNA: What lessons can Muslim women—and indeed all believers—draw today from Lady Fatima’s example of steadfastness and piety?

Gabby: As a non-Muslim woman, I can only speak about the lessons that I myself have drawn: patience under suffering; speaking out against injustice when it is necessary; the recognition that great fame, wealth, and accomplishment in one’s own lifetime are not the real treasure, but rather one’s spiritual stature, which may be accompanied by seemingly lowliness and humility; the notion that devoting one’s self to one’s family is a worthwhile endeavor, even while it can be accompanied by other activities.

IQNA: Fatima’s eloquent Sermon of Fadak is often cited for its intellectual and theological depth. How do you interpret the sermon’s significance in the context of early Islamic authority and women’s voice?

Gabby: It is difficult to overestimate the significance of Fatima’s Sermon of Fadak. First, the speech provides an example of a woman addressing the entire Muslim community about a pivotal matter, and not shying away from voicing her (somewhat) controversial opinions. From that standpoint alone, it deserves to be studied and held up as an example for those who would claim that women in Islam lack rights and authority.

Second, its impact has been far-reaching. As I have already mentioned, medieval scholars such as Ibn Babawayh and al-Majlisi cite it in their hadith collections, indicating that they saw her as a religious authority.

Read More:

More recently, the Iraqi Ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr claimed that Fatima was the very first to openly critique the ruling party. He praised her very highly and attributed to her a sort of infallible sense of how the caliphate should be structured.

Other contemporary Shi‘i scholars have pointed to the sermon’s utility as a means of teaching people about the strength of the women of the ahl al-bayt. I think that the significance of the sermon has been felt for a long time, and will continue to be felt.

IQNA: Your research draws on both Sunni and Shia sources. What shared values or historical truths about Lady Fatima do you think unite Muslims beyond sectarian boundaries?

Gabby: I think all Muslims can appreciate Fatima’s devotion, piety, wisdom, and self-sacrificing nature.

It is true that the Shia tend to assign her an extremely exalted stature but that does not mean that Sunnis cannot also appreciate her qualities and her role in historical events, such as her fierce defense of the Prophet, her loyalty to him and to her husband and children, and even the interpretation of Quranic verses to refer to her, such as that of Al-Kawthar.

It is significant that within pre-modern Sunni societies such as that of the Ottoman Empire, she is afforded great respect. For example, an endowment deed for a mosque complex built by the Ottoman princess Mihrumah Sultan compared the princess to Fatima in innocence. The same deed stipulated that Fatima should be regularly remembered in the prayers conducted in the mosque.

In fact, the impetus for my writing of this book was the mention of Fatima by the Sunni Indian poet Amir Khusraw (d. 1325) in a brief poem in which he praises the daughter of the Prophet -- a clear indication of the reverence in which she is held by Sunnis and Shia alike.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview are solely those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of International Quran News Agency.

Interview by Mohammad Ali Haqshenas