Author Highlights Lady Fatima as a Universal Role Model for Humanity

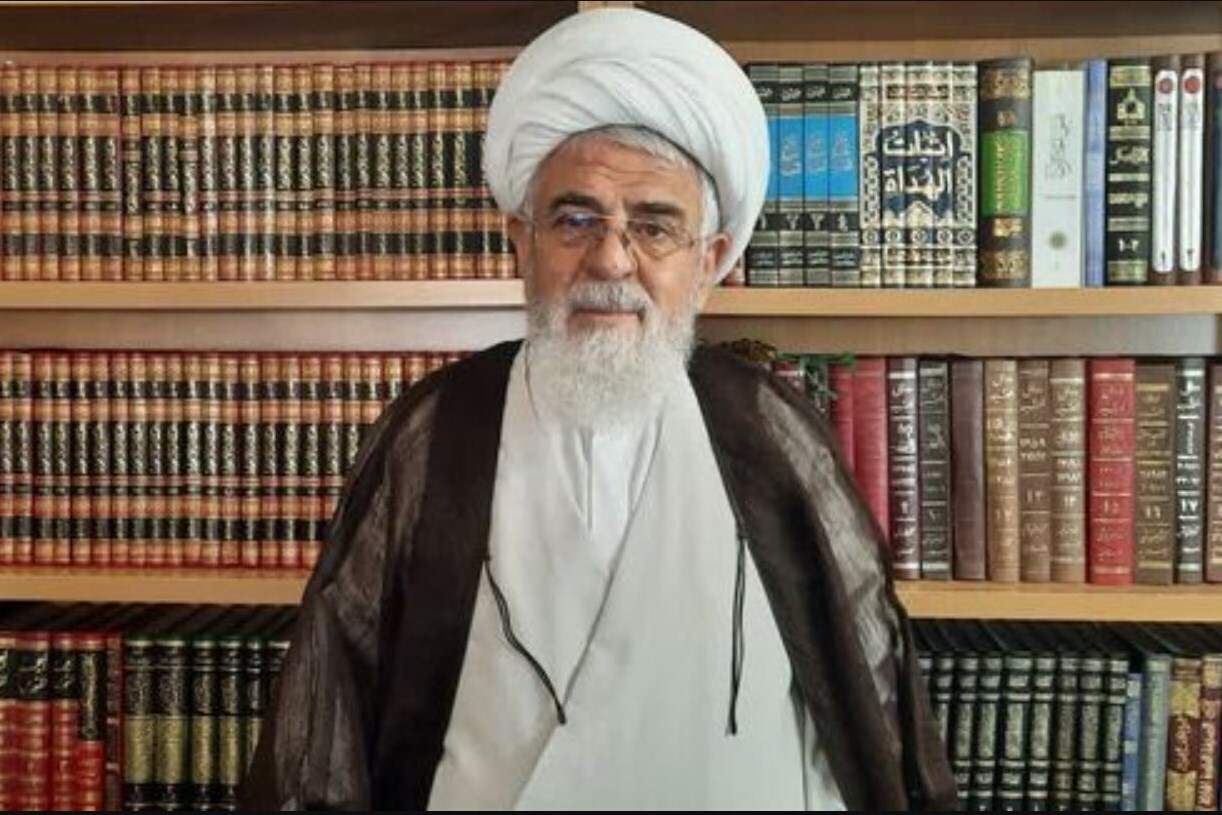

In his book Fatima (SA); the Ever-Flowing Spring of Existence, author Hojat-ol-Islam Ahmad Zamani connects Lady Fatima’s (SA) life from childhood to her stewardship in economic and social spheres.

Zamani explains that his guiding principle in the book is the saying attributed to Imam Hassan Askari (AS): “Our mother Fatima (SA) is our model from among the Ahl al-Bayt (AS),” and notes that this statement “always remains for all of us a paradigm.”

He adds that he has reviewed various narrations about her age at death—whether 18, 24 or 27 years—and concludes that “it can be said she was about 24 years old.”

He emphasises that Fatima’s (SA) exemplary nature emerges through the different stages of her life: childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, the period pre-marriage, the time of the Prophethood and even the period before his mission.

“In the book I have brought that,” he says, “and in some respects I show that Fatima (SA) was present even when more than five thousand verses had been revealed in Mecca—unfortunately many writers have overlooked this point.”

Read More:

Zamani examines Fatima’s (SA) childhood in Medina, noting that she was about 12 years old when she arrived with Imam Ali (AS) after the Prophet’s (PBUH) migration. He draws the reader’s attention to the fact that even girls at that age in today’s families speak and contribute. He challenges assumptions about her silence or passivity.

Turning to economic stewardship, he asserts that in her marriage to Imam Ali (AS), “she was the wealthiest woman in Medina. Not only Fadak but half of Medina was at her disposal.” Yet, he says, the abundance did not lead to personal luxury: “She never treated it as personal property; she devoted it all to the needy.”

Zamani draws on sources—including reports from Sunni narrators—that suggest Lady Fatima (SA) was involved in discussions about the verses of the Quran. He writes that she appeared in scenes of revelation and even in gatherings as a child when the Prophet (PBUH) spoke with her directly.

For Zamani, the implication is clear: “When we say Fatima (SA) is the model for the women of the world, we must attend to all aspects of her life.”

Read More:

He insists that her economic acumen is not a later attribution but part of her documented legacy: “The division of property, attention to the poor and precise financial management all show that she was a knowledgeable economist in every sense.”

His book invites all daughters and women of the Muslim community to reflect that childhood has an ontological philosophy—how to follow a father, how to embody his mirror-image, and how to look to a mother such as Khadija (SA).

In Zamani’s view, Lady Fatima (SA) stands not only as a late child of the Prophet (PBUH) but as a conscious and engaged adult whose life remains relevant for Muslims today.

In presenting Fatima (SA) as “the ever-flowing spring of existence,” Zamani offers a holistic portrait: one that combines spirituality, scholarship, social justice and economic responsibility in a single figure. His hope is that readers—male and female—will recognise her as a legitimate and universal model for faith and action in the modern world.

Read More:

Thus, the narrative forefronts both reverence and practical lessons. It invites the Muslim reader to engage with Fatima’s (SA) legacy not as a distant emblem, but as a living guideline.

The book underscores that her wealth, her early awareness of responsibility, her deep engagement with the prophetic household and her unwavering focus on service all converge to present an enduring role-model.

4314527