Islamic Literature ‘Unexploited’ Terrain for Exploring Quranic-Biblical Links: Professor

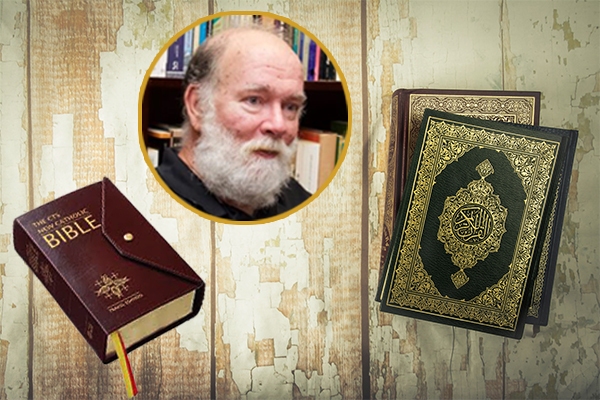

John C. Reeves, Blumenthal Professor of Judaic Studies and Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, shared these insights during an online lecture hosted by the Inekas Institute on September 6, 2024.

A North Carolina native, he joined UNC Charlotte in 1996 after serving as a faculty member at Winthrop University. His research explores the intersections of Near Eastern fringe groups, apocalyptic traditions, and religious dualism in late antiquity and the medieval period.

“Islamic literature, especially its post-Quranic expressions, offers a very fertile and still largely unexploited site for the student of the lore that connects Bible and Quran,” Reeves asserted, encapsulating the core of his discussion.

He emphasized the emergence of Islam in the Near East as a continuation of existing monotheistic traditions rather than a sudden rupture.

He encouraged students to explore the connections between Islam and the religious currents of the Roman, Iranian, Aksumite, and South Arabian communities during the 6th and 7th centuries.

Read More:

Reeves discussed the familiarity of the Quran with various scriptural traditions circulating in the world, emphasizing the need to understand the historical and cultural processes surrounding the formation of Near Eastern scriptural texts and canons.

There is no singular "Bible" but rather a variety of biblical texts that differ in content, structure, and regional distribution, he said, adding, this challenges the assumption that the Bible was a fixed collection prior to the 7th century.

“The Quran… seems to endorse the idea that Jewish and Christian scriptures comprise a more extensive library of titles than is anachronistically projected onto 7th-century Arabia by modern scholars,” he said.

The scholar said it is important to understand the cultural contexts in which different biblical texts were used. For example, different communities, such as Ethiopian Christians, had distinct biblical canons that differed significantly from those of other regions, he added.

Read More:

He pointed out that many scholars misunderstand the historical and cultural processes surrounding the development of scriptural texts, leading to overly simplistic conclusions about the relationship between the Quran and earlier scriptures.

“We do, however, need to think about and approach the interpretation of likely characters, scenes, motifs, or themes, even verbiages, in a more carefully nuanced and targeted manner than has usually heretofore been the case. This means that arguments that are going to posit a connection between a Quranic locution or depiction and a Jewish or Christian scriptural source should exercise precision and go well beyond just vague generic affinities, which when all is said and done actually really add nothing concrete to our understanding about the intellectual background of the text of the Quran.”

Reeves also touched upon the complexity of religious identities in the Eastern Roman and Sassanian worlds, cautioning against using broad labels like "Jews" or "Christians" without considering the regional and cultural differences that existed among these groups.

Jewish, Christian, and Islamic communities were not isolated at the time, he said, adding that they interacted, adapted, and borrowed from each other's literary traditions.

Read More:

In his lecture, Reeves provided examples of similar references in the Quran and earlier scriptures, such as the narratives about prophets including Abraham, Moses, and Enoch (Idris).

Further delving into the description of Idris, he said that Islamic literature frequently associates Idris with scribal traditions and moral teachings, echoing Jewish and Christian stories of the figure.

“Extra-biblical traditions about Enoch or certain popular traditions tied to his name, like those that feature rebel angels and their interactions, circulated widely within Muslim circles and even continued to develop in new directions,” Reeves stated.

He cited the Arabic Sunan Idris and references to Enochic traditions in Iraq and Kufa. However, Reeves believed that the Quran itself shows minimal direct dependence on Enochic texts like the Book of Enoch. “Almost all examples which scholars have proposed to date can just as easily be explained without invoking any kind of direct reliance on any of these apocryphal Enochic books,” he said.

He noted that the Quran's narrative structure and themes often intersect with those found in earlier Jewish and Christian texts, indicating a shared literary heritage. For instance, the Quran's portrayal of figures like Abraham and Moses reflects themes present in both Jewish and Christian literature.

Read More:

The scholar advocated for a more nuanced approach to studying the Quran's intertextual relationships.

He warned against simplistic assumptions that any Jewish or Christian tradition must be older than its Islamic counterpart, emphasizing the need for careful analysis of the historical contexts in which these texts were produced.

Pointing to the importance of exploring early Islamic traditions and their possible connections to earlier scriptural texts, Reeves said he believed many early Islamic scholars were well-versed in the biblical traditions and that this knowledge could have influenced their interpretations of the Quran.

Reeves concluded by emphasizing the importance of studying these shared traditions to gain a nuanced understanding of Islamic and biblical texts.

“Occasionally such sources can be readily identified, even though the precise means whereby a particular text entered this new linguistic tradition cannot be reconstructed with certainty,” he remarked.

Please note that the content reflects the views of the scholar and does not represent the views of the International Quran News Agency.

Reporting by Mohammad Ali Haqshenas