Researcher Stresses ‘Creativity’ of Quran in Repurposing Biblical Phrases

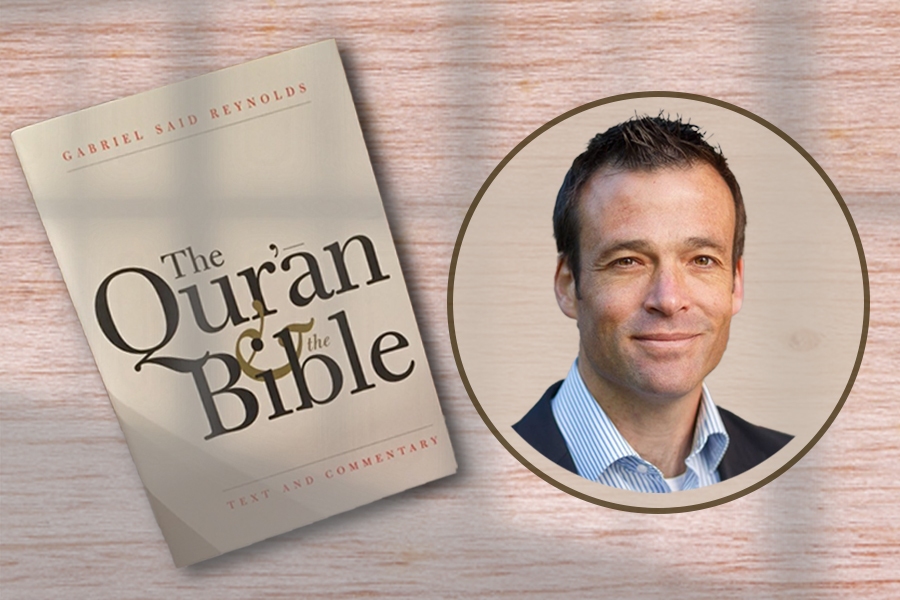

This is according to Gabriel Said Reynolds who made the statements while addressing an online lecture hosted by the Inekas Institute in late August 2024.

Reynolds, a professor of Islamic studies and theology at the University of Notre Dame, explored how certain phrases and theological ideas found in the Bible appear in the Quran—sometimes directly, sometimes as transformed references—arguing that these echoes are neither accidental nor evidence of dependence, but rather signs of the Quran’s creative engagement with its religious context.

Early in his speech, he pointed to the importance of mutual understanding and academic collaboration. “There are misunderstandings and suspicions, both ways,” he said, referring to the distance between Western academia and Muslim-majority contexts. “It’s an act of grace and trust to invite me to this.”

Reynolds, who specializes in Quranic studies and its historical context, structured his lecture in three parts: a brief overview of the Bible, examples of biblical phrases found in the Quran, and a reflection on what these intertextual echoes reveal about the Quran’s context and audience.

Read More:

He began by clarifying the nature of the Bible as a literary anthology, noting its wide array of genres and languages. “The Bible is more a library than a book,” Reynolds explained, highlighting the distinctions between the Hebrew Bible, the Christian Old and New Testaments, and the religious texts circulating in the centuries before Islam.

He pointed out that Jewish and Christian traditions also included literature outside canonical scriptures—such as the Mishnah, Talmud, apocryphal gospels, and Syriac theological writings—which were widely read in the Middle East before and during the rise of Islam.

“The real problem with scholarship on the Quran and the Bible is people taking the easy way—looking only at the canonical Bible and the Quran,” he said.

Biblical Phrases Reimagined in the Quran

The core of the lecture focused on specific biblical phrases that appear in the Quran—similar in language, yet often repurposed for new theological messages.

One example was the metaphor of “the camel passing through the eye of a needle”, found in the Gospels as a critique of wealth. In Matthew 19:24, Jesus is quoted saying: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”

The Quran uses a similar image in Surah al-A‘raf (7:40), but with a different focus—rejecting divine signs rather than criticizing materialism. “Indeed, those who deny Our signs and are disdainful of them—the gates of the heaven will not be opened for them, nor shall they enter paradise until the camel passes through the needle’s eye,” reads a translation of the verse.

Another instance is the Quranic phrase “kulubunā ghulf” (our hearts are uncircumcised), which appears in Surah al-Baqarah and Surah al-Nisa. Reynolds drew a connection to the biblical theme of “circumcision of the heart”—a spiritual metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and Pauline epistles encouraging internal, not just ritual, piety.

“God wants more than this,” Reynolds explained. “It’s not just observance of the law in an outward manner, but obedience, submission, love of God in an inward manner.”

Read More:

He noted parallels between Quranic passages and the speech of Stephen in Acts 7, who accuses his Jewish audience of resisting the spirit by having “uncircumcised hearts.” Similar expressions appear in Syriac Christian texts, further showing the shared linguistic and theological environment of the region.

Reynolds argued that these examples show the Quran is not copying earlier scriptures but entering into theological dialogue with them. “The Quran is using the same turn of phrase, but in a completely different argument,” he said, noting the originality in how the Quran adapts these expressions.

Theological Creativity, Not Imitation

Reynolds notes that the presence of biblical language in the Quran should not be read as evidence of dependency or imitation. Rather, it illustrates how the Quran operates within a broader religious discourse, reusing familiar phrases in original ways.

He cited the metaphor of the mustard seed, found in both the Gospels and the Quran. In the New Testament, the mustard seed represents the internal and expansive nature of faith. In contrast, the Quran uses it to emphasize God’s perfect awareness of even the smallest deeds (Surah Luqman 31:16 and Surah al-Anbiya 21:47).

“As with the camel and the eye of the needle, the mustard seed is used in a new and different way in the Quran,” Reynolds said.

Other examples included the expression “no soul knows what has been hidden for it” in Surah al-Sajda (32:17): “No one knows what delights have been kept hidden for them [in the Hereafter] as a reward for what they used to do” which resonates with 1 Corinthians 2:9: “What no eye has seen, what no ear has heard…”

A similar sentiment appears in a Hadith Qudsi, further suggesting a shared theological motif across religious traditions.

Reynolds highlighted a striking phrase in Surah al-Baqarah where the Quran contrasts the disobedience of the Israelites—“We hear and we disobey.” This, he argued, reflects a subtle linguistic play on Hebrew terms found in Deuteronomy and Exodus, where the Israelites say “We hear and we do.”

The researcher called this an example of the Quran’s creative reinterpretation of scriptural language.

Read More:

Toward the end of the lecture, Reynolds addressed the broader implications of his findings. He pushed back against old Orientalist assumptions that the presence of biblical content in the Quran proves exposure only to “heretical” or “corrupt” Christian groups in Arabia.

“There’s nothing in these turns of phrase that proves in any compelling manner that the Christianity of Arabia was not standard Christianity,” he said, criticizing views that depict early Islam as responding only to marginal or deviant religious ideas.

Instead, Reynolds proposed that the Quran should be viewed as engaging with widely recognized religious language to make its arguments heard. “These were useful ways of signaling a theme or an idea to the audience,” he said. The familiarity of the phrase would capture attention, while the Quran would redirect its meaning toward a new theological point.

This approach, he argued, reveals how the Quran functioned in a multi-religious environment marked by disputation—a term he used to describe the Quran’s dynamic engagement with contemporary beliefs.

“The Quran needed to make space for itself by repurposing or appropriating turns of phrase that would have been well known,” Reynolds explained.

“The takeaway here is the originality of the Quran, the creativity of the Quran, the disputational nature of the Quran, but also, the Quran as an active, creative player,” he stressed.

Read More:

Reynolds concluded with a reflection on the Quran’s attitude toward Christians. He pointed to passages in Surah al-Hajj and Surah al-Nur that express concern over the destruction of religious buildings, including churches and monasteries.

The Quran defends these buildings not in abstract terms, but because “the name of God is mentioned” in them. “Something good happens in these buildings,” Reynolds noted, quoting the Quranic phrase “yudhkaru fīhā ismullāh” (wherein God’s name is remembered). He also highlighted how monks, who dedicate themselves to remembrance rather than commerce, are praised for their devotion.

These passages, he argued, suggest that while the Quran challenges certain Christian beliefs, it also acknowledges their piety and sincerity. “The Quran, while it disputes with Christians, its assessment of Christians is not always negative,” he noted.

Please note that the content reflects the views of the scholar and does not represent the views of the International Quran News Agency.

Reporting by Mohammad Ali Haqshenas